Author: David Skrbina

Too often, it seems, matters of population are overlooked in discussions of global sustainability. And this is true, despite some rather obvious points: A world of, say, 5 billion people is more likely to be sustainable than one of 10 billion; and a world of 1 billion is likely more sustainable still. All things being equal, a world with fewer people will allow for a more robust planetary ecosystem, and a higher quality of life for humans, than a world with more people. Few seem willing to state things this clearly, but I think few would contest it, if pressed.

Currently the Earth is at roughly 7.7 billion, heading to 9.5 billion by 2050, and perhaps to 11 or 12 billion by 2100. Each year about 135 million babies are born; if we subtract the 55 million annual deaths, we get an annual growth rate of 80 million—or around 220,000 more humans every day. Every one of these people needs clothing, shelter, food; they produce waste; they buy things and discard things; and they compete for space on this planet with all other animal and plant life. As we see from mass extinctions and general reductions of animal life in particular, humans are slowly but surely squeezing out all other lifeforms on Earth. This is not a recipe for long-term sustainability.

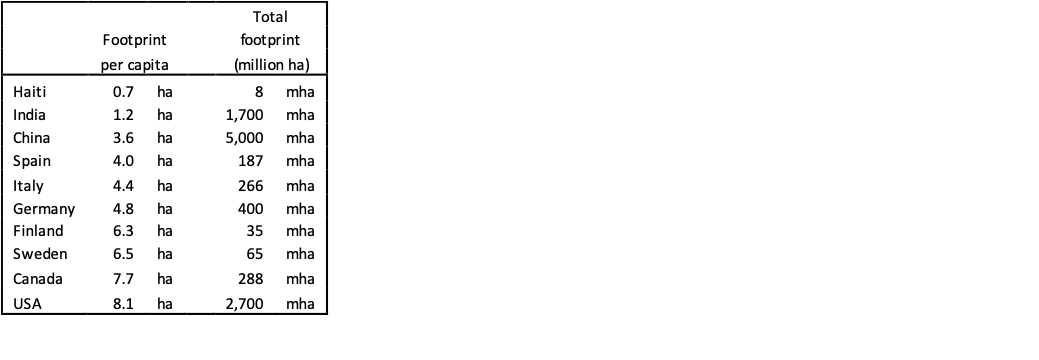

But it’s not just human numbers, as we know. It also depends on how much each person produces and consumes—their standard of living, and specifically how much of the Earth’s resources each requires, on an on-going basis, to support their lifestyle. This aspect has been factored into the ecological footprint: a measure of land-area equivalent, per person, that represents the average resource use of each person in a given nation. Thus, 10 million people with a high footprint are more ecologically damaging, and hence less sustainable, than 10 million with a low footprint. It is well-known that wealthy, ‘first world’ industrial nations have higher footprints, and poorer, ‘third world’ nations much smaller ones. At the low end, we have nations like Haiti, that survive on the equivalent of just 0.7 hectares/person. India consumes a bit more (1.2) and China more still (3.6). European countries are higher still: for example, Spain (4.0), Italy (4.4), Germany (4.8), Finland (6.3), and Sweden (6.5). At the high end of major nations, we have Canada (7.7) and the USA (8.1).[1] There is naturally some variability in such numbers, and their precise calculations can be questioned, but they seem to provide useful directional figures.

From a global standpoint, what matters is the total footprint of each nation, and ultimately, the total footprint of all humans. Calculating national totals is simple: per capita numbers (above) multiplied by current population. The total footprint of Haiti, then, is (0.7 x 11.2 million =) 7.8 million hectares. Figures for all nations listed above are as follows:

Constructing a Plan

My concern here is to sketch out a nation-by-nation plan by which each country can establish concrete, achievable numbers to get to long-term sustainability, using a common standard. This will allow a nominally “fair and equal” approach, and hopefully will avoid pitting the wealthy north against the poorer south. Thus we need not point fingers at China, for example, and say that they have the largest global footprint, and therefore that “they need to do something.” It’s not that simple. Everyone has a role. Thus, we need a fair and reasonable plan, on a universal standard, that each nation can pursue on its own.

One way to do this is to establish clear and intuitive standards for sustainability. Here is one approach that I have long championed: Compare a nation’s total footprint to the land area that they have. As we might guess, many nations are “overstepping their bounds,” and living on more land area than they actually represent. Take the USA. Discounting Alaska—which is huge, sparsely populated, and mostly mountains or frozen tundra—the US has around 810 million hectares of land. And yet, as we see above, the total footprint of the US is about 2,700 million hectares. Hence they are over-using land by a factor of 3.3; in other words, Americans use more than three times as much land as they have.

How is this possible? Partly by overtaxing their land, and partly via that economic practice known as globalization. On the one hand, America uses its own non-renewable resources (like coal), and uses its renewables at a faster rate than they can be replenished. Additionally, America’s vast international corporations stretch out across the planet, acquire resources, and bring them back for local consumption. Oil, machinery, hardwoods, precious minerals, food, technological devices…all these are purchased abroad and imported into the US for consumer and industrial use. Obviously, this is an unsustainable situation. It is not a global model. Every nation cannot overstep its consumption; there is only one Earth, after all.

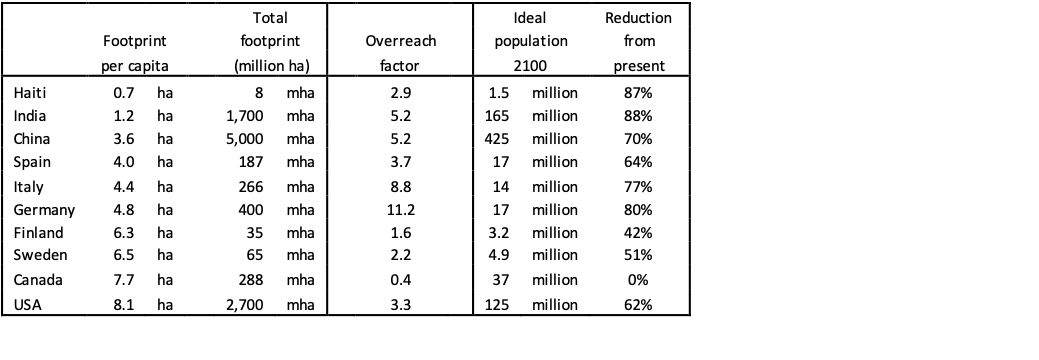

How do others fare? Thanks to advanced technology and globalization, America is not alone. India has about 330 million ha of land, and thus overreaches by an even larger factor of 5.2. China has around 950 million ha, and thus overconsumes by a similar factor. Figures for the nations in question are listed below:

For the northern nations (Finland, Sweden, Canada) I have subtracted roughly one-third of their formal land area, being, like Alaska, largely frozen or otherwise unusable land.

Such figures are, of course, very rough numbers, but they do give us valid directional information. All but Canada are overreaching their bounds, and hence are unsustainable on this basis alone. Germany stands out here as being deeply unsustainable, with Italy not far behind. I hasten to note, however, that ecological overreach is not primarily a rich-nation phenomenon. Even impoverished Haiti, with its dense population and mere 2.8 million ha of land, overreaches by a factor of 2.9. This partly explains why, at present, humanity is consuming the equivalent of 1.75 Earths—a situation guaranteed to lead to catastrophe.

A first step toward true sustainability, then, would be to require each nation to live within its own area. Or rather, equivalent land area; clearly there can be mutual trading, where each nation “uses” some amount of land area elsewhere. But ideally it should be net zero—no net imbalance.

But this step alone is insufficient, because it presumes usage of all of a nation’s land area. The US, for example, cannot sustainably use its 810 million ha because soon enough, the land would be exhausted. They cannot farm, pave, develop, harvest, or graze every bit of land they have. Large portions are functionally unusable (desert, mountains, swamps, etc), and much needs to be protected, for the sake of nature. Much less than the 810 million ha can used, sustainably, in the long-run.

So, we arrive at a key question: How much less? In other words, How much for nature? Setting aside the oceans, how much of Earth’s land area does nature ‘need’ to do her work? Large swaths, to be sure. Large carnivores need vast areas of contiguous land with little or no human presence. Migrating animals need the same. Forest ecosystems flourish best in large, undisturbed areas. Wildfires must be allowed to burn on their natural schedules, in vast regions, to restore the vitality of the soil.

So, how much? How much would be fair and yet still get the job done? Here’s one proposal: 50/50. That is, half for humans to use, and half for nature to do what nature does best. On the face of it, this might seem fair, but of course objectively it’s not. That one species among millions should be allowed to dominate half the Earth is, in fact, an outrageous assertion. It speaks to the gravity of our situation that 50/50 should even pretend to be ‘fair.’ For now, though, it will serve our purposes.

I’m not alone in this call, incidentally. Prominent biologist E. O. Wilson has notably defended a similar figure, in his proposal of “half-Earth.” See his 2016 book of the same name, and the organization he established online at www.half-earthproject.org. Again, this is a very rough guideline, but as a concept it is simple and coherent: half for nature, half for humanity. And it just might work.

Two Core Principles

All this boils down to two essential principles of global sustainability:

Each nation should set aside half of its land area, as wilderness or protected land.

Each nation should adjust its population and consumption to live on the other half.

This is simple, clear, intuitive, easy to convey, and workable. At the very least, it can serve as a vision moving forward—certainly it is far ahead of anything being attempted at present.

So, in rough numbers, what does this actually mean? The principles are straightforward, but for many nations, the challenge would be steep. Take the USA. If America were to be truly sustainable, it would begin to set aside some 400 million ha as wilderness, national park, or protected land. Obviously this cannot happen quickly, but given, say, until the end of the century, it is eminently workable. Setting aside 2 or 3 million ha annually would reach the desired goal relatively quickly, given that several million hectares are already under some form of protection.

Harder would be to reconfigure American society to live on the other 400 million ha. It has three options: (1) reduce population, (2) reduce per capita footprint, or (3) some combination of the two. Let’s say Americans want to continue to live at their luxury level of 8.1 ha per person. No problem—they just need to have less people. A lot less people. The math is straightforward: 400 million ha divided by 8.1 allows just 50 million people. This is a breath-taking 85% reduction from present levels—in a nation that is currently growing by some 4 million people annually.

Impossible, you say? Fine, we have an alternative for them: reduce per capita consumption. Let’s say Americans want to keep all of their current population of 330 million people. No problem—they just need to consume less. A lot less. Again, the math is clear: 400 million ha divided by 330 million people allows an average footprint of 1.2 ha per person. This is roughly the level of present-day India. Such is the math. The numbers are relentless.

Fortunately option #3 is more palatable, especially if implemented over, say, 80 years. If both population and footprint were reduced by a small amount, consistently, every year, America could reach sustainability in 80 years. And easily. For example, if both were reduced by just 1.2% annually, in 80 years—by the year 2100—America would be at a population of 125 million with a footprint of around 3.0 hectares per person. Its total footprint would then be at 375 million ha, effectively a sustainable figure. And if the other half of its land were placed into protection by that time, the US would be a model nation for the world.

Similar analysis holds for other countries, with appropriate modifications. Take India. With a land area of 330 million ha, India should set aside half for nature, and then live on the other half—on 165 million ha. On the one hand, an annual reduction of 1.5% over 80 years in both population and footprint would work. But this would yield an unacceptable footprint of 0.36 ha/person—about half of present-day Haiti. Probably something like 1.0 ha/person is the bare minimum to maintain anything close to a civilized existence; less than that, and we are looking at mass poverty and mass starvation. Therefore India’s task is nearly all on the population side of the ledger. Consequently, they would need to get their numbers down to 165 million, roughly, to reach sustainability. Today they are at 1.4 billion. Over 80 years, this requires a 2.75% annual reduction—a challenge, to be sure, but not impossible.

And then consider Finland. If we take its usable land area of 22 million ha (again, neglecting the frozen north), and set aside 11 million for nature, and then use the other 11 million for human sustenance, the numbers are very manageable. A mere 0.7% annual reduction in population and footprint would arrive at figures of 3.2 million people (versus a current figure of 5.5 million) and 3.6 ha/person. Finland, in fact, is already trending downward in population, according to EU estimates. Projections are now officially “bleak,” with a projected loss of some 100,000 by 2050 and another 100,000 by the end of the century. And yet, from a sustainability perspective, this trend is positive and needs to be reinforced, not resisted.

Here is the full chart, with “ideal” populations in the year 2100, along with percentage reductions from present.

Note: Numbers for Haiti and India have been modified to keep their per capita footprints from falling below 1.0 ha. And Canada alone shows no necessary reduction, given that they are already far below their limit—i.e. that their overreach is today below 1.0. But most nations will necessarily have to plan for a significant long-term reduction, albeit at a small (1 – 2%) annual rate.

Next Steps

Clearly there is more to be said, and many details to examine. But I think, directionally, this gives us some important facts to consider in the broader context of sustainability. For example, the need to shrink both footprints and population is naturally compatible with the ‘degrowth’ movement, which certainly needs to look beyond merely economic concepts like per capita GDP and examine population and nature directly. Within the SUCH network, I would be happy to collaborate with others on further discussions along the above lines. I would suggest that we all need to keep in mind population and footprint issues, in our larger fields of work.

From a governmental standpoint, it seems that most talk these days is around climate change and the need to become “carbon neutral.” For example, Finland recently committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2035, which makes it one of the most ambitious plans in the world. But there is a danger here: The implication here that carbon neutrality alone will solve the climate crisis, and perhaps even the global ecological crisis as well. Unfortunately such a plan, though welcome, is far from sufficient. First, we have been pumping carbon gases into the air for over 300 years, and neutrality only means no further additions; at some point, we need to start pulling carbon out of the air, and return to a stable condition. We need a “carbon negative” plan, not a carbon neutral one. Second, the implication is that population can continue its unhindered growth—as if a world of 10 billion “carbon neutral” people could be sustainable. It can’t.

But this raises an important question: How many people can the planet sustain? We can do a quick analysis, comparable to what I have done above. The total usable land area on Earth is around 11.2 billion ha. If we set aside half (5.6 bha) for nature and live on the other half, and we assume the current global average footprint of 2.8 ha/person, then the planet can support just (5.6 / 2.8 =) 2 billion people at current living standards. This is a decline of 74% from the current 7.7 billion—a figure that is very much in line with the national reductions I listed above.[2]

Furthermore, this suggests the need to set national and global targets for both population and footprint. Both are currently rising: global footprint at 2.1% per year, and global population at 1.0% per year. Rationally, we should accept the need for halting the growth curves and then implementing long-term reductions. This implies setting a target date for a population peak, and then goals and plans to bring it down. The same idea, incidentally, has recently been proposed with respect to meat-eating—meat being especially destructive, ecologically. Scientists have proposed a “peak meat” date of 2030, after which global (and presumably national) meat consumption would decline. We can do the same here. Let’s propose a “peak population” date of 2030, after which we can map out a decline to sustainable levels. Then we can push national governments to commit to such a target, and begin to implement plans to make it happen.

It goes without saying that there are many potential criticisms of such an approach, and these must be considered and responded to. Given the substantial reductions in both population and standard living that I propose here, I can imagine that they will be harsh indeed. But my general response is this: If we don’t like this road to sustainability, what would be better? That is, what true plan for global sustainability can afford to overlook population reduction? I can’t imagine any realistically sustainable Earth with 5 or 10 billion people; such an idea seems absurd. Population must go down—either voluntarily, slowly, and rationally, or else nature is likely to do the job for us. And she won’t be kind. Thus, if population is inevitably going down, the best case is a slow, fair, and reasonable approach. This was my motivation here.

Finally, I must point out that there is one wild card in this whole discussion: technology. Even if, by some miracle, humanity began to move in the above direction and reduced both population and footprint, and expanded wilderness, technology may well continue its relentless advance. There are many scenarios where accelerating advanced technologies pose literally existential risks to humanity and the planet, and in a time frame sooner than the above plans require. In other words, our best efforts on population may be rendered moot by some technological disaster. Hence, we cannot ignore that component. In parallel to the above, I would suggest that we need a comparable scaling-back of industrial technology, slowly but steadily, to minimize the risk of any such technological catastrophe. But that’s a topic for another time.

Meanwhile, I am happy to collaborate with anyone on the issues examined here.

[1] 2016 data, from Global Footprint Network.

[2] Obviously, we could sustain a higher population if we reduced the global average footprint. Theoretically, 5 billion people are sustainable if they all live at the poverty level of 1.0 ha/person. But that’s not a viable goal.